Clik here to view.

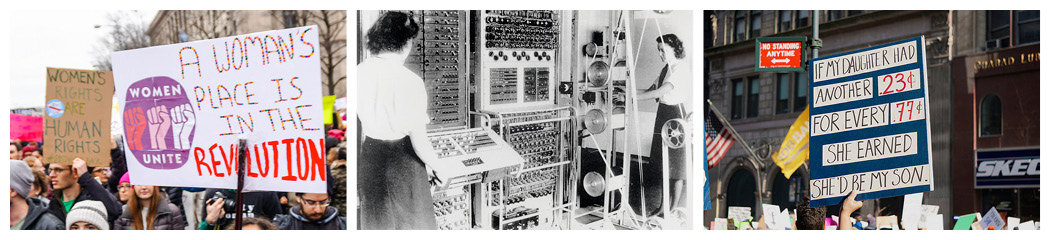

Images from the March 9 Women’s Strike and Female Scientists (center), available under a Creative Commons license.

On the morning of March 8, 2017, I, like many women around the country (and perhaps the world) faced a particular question: should I go to work? On this particular day, the question was triggered by International Women’s Day and its attendant call for a women’s strike. Named “A Day without Women,” the strike aimed to highlight both the vital role that women play in the the domestic and global economies, and the ways gender discrimination continues to plague the United States and the world. In the workplace, specifically, women often face lower wages, sexual harassment, discrimination, and job insecurity that their male counterparts do not.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

My work–the labor for which I get paid–is teaching, an industry and practice very much gendered as “female.” From a cultural studies perspective, we can easily map feminized practices of childcare and child-rearing onto contemporary practices of children’s education. From a statistical perspective, this is even more easily mapped, as the most recent accounting by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that nearly 75% of elementary and secondary educators are female. This distribution of labor undoubtedly made the Women’s Strike more effective, as some school districts found themselves with no choice but to cancel classes, given the number of female employees that opted to strike. If necessitating the cancellation of class does not demonstrate the role that women play in the work of education, then I do not know what does.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

Though I am a teacher, I do not work in elementary or secondary education. I teach postsecondary students at a four-year research institution: the Georgia Institute of Technology. As of 2015, 281 of Georgia Tech’s 1140 faculty members were female. This is roughly 25%–a notably lower percentage of female faculty than 2013’s national distribution of 45%, as reported by the NCES. Both 25% and 45%, however, stand in stark contrast to the 75% of elementary and secondary educators who are female. Further, just as this 75% reflects cultural assumptions of childhood education as a feminized practice, so too do these 25% and 45% reflect cultural assumptions of postsecondary education–or perhaps more accurately, the practice of researching on which this education is based–as a masculinized practice. Effectively, though I work in an industry that can be broadly described as a “female-dominated workplace,” the specifics under which I work would be more accurately described as a “male-dominated workplace,” a differentiation with multiple consequences, two of which are relevant here. First, if I strike, there is no guarantee that my political action will have the same effects of disrupting the workday, and forcing class cancellation or substitution. Second, something sits uneasily about participating in an event called “A Day Without Women,” when this participation would further absent oneself from an industry and workplace that is, if not entirely “without” women, certainly lacking in them.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

This semester at Georgia Tech, I am teaching multiple sections of one class: Technical Communication and Software Design Strategies. Cross-listed between the College of Computing (CoC) and the School of Literature, Media, and Communication (LMC), this two-semester course leads students majoring in either computer science or computational media through the software development process from conception to completion. The students work in development teams to build a software system for what is typically an extracurricular client. Alongside this software system, students also learn to produce industry-standard technical and professional communications, all of which are designed to critically guide their development and design processes, and communicate these processes to their client. To complement its cross-listing, the course is co-taught by a faculty member from CoC, and one from LMC. This means that there would be no need to cancel class or seriously disrupt students’ workdays if I didn’t show up. It also means that I have the privilege of striking, as there would be no requirement that I make up these lost contact hours with students–a deterrent for a professor in Iowa. Indeed, if I don’t show up, the students could (and would) still learn about usability heuristics; they would just learn about them from my co-teacher, rather than from the two of us.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

My co-teacher is an older, male Computer Science instructor with something in the neighborhood of 15-20 years of experience in the software development industry. I, on the other hand, am a young, female, freshly-minted PhD and first-year postdoctoral fellow. On any given day, we share the instructional space of the classroom; I focus on technical communication strategies, while he focuses on software development and design. This semester, we have 94 undergraduates, split between two sections. Out of this 94, 20 (roughly 21%) are female, with about 10 female students in each section of the class. According to Georgia Tech’s enrollment data for 2015 (collected based on the Fall semester), this percentage is reflective of the College of Computing in general, with just under 22% of its students (408 out of 1877) reporting their gender as “female.” Notably, this distribution is not inconsistent with the software industry at large. Indeed, looking to industry, this percentage will lower slightly, with women comprising 17% of Google’s technical employees, as compared to Facebook’s 15%, Apple’s 20%, and Microsoft’s 26.8% (this number reflects Microsoft’s global workforce, as they did not report their technical-specific workforce). Perhaps more disturbing is a recent report stating that, in Silicon Valley as a whole, women hold only 11% of executive positions — precisely those positions of power and influence that Georgia Tech prepares its students to fill. Besides bringing the class one body closer to “A Classroom Without Women,” my absence on this day would also equate to one less student contact hour with a woman of relative power and influence. I am not a tenured or celebrated faculty member; I’m neither famous, nor a software engineer. But I am at the front of the classroom, and I do hold a doctoral degree. In fact, I am the only person in our classroom who does.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

I am reminded of a student who visited me in office hours during my first week at Georgia Tech. Quiet and unassuming, she came into my office to talk about her professional biography. She told me about her interest in and concerns about representations of women in STEM, noting that she and a group of female friends had recently read and been inspired by Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. She then asked me about my research and my experiences in graduate school, eventually commenting on the rarity of encountering female faculty, and how empowering it must have been to receive both a PhD and this postdoc at Georgia Tech.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

I also remember a more recent office hours visit, as a student came in to talk about her team management module. She was frustrated, feeling that her team was not doing the work she expected them to be doing, and was worried about the quality of the team’s deliverables, and how this would affect her grade. Over the course of our conversation, these frustrations eventually clarified into something exponentially more frustrating than a grade: her personal challenges in leading a team of mostly male engineers, none of whom (she felt) really listened to her or considered her opinions. Indeed, she felt like she had to become someone she didn’t want to be–a bossy, mean, nasty woman–to avoid being talked over completely in group meetings. Given the state of industry, there’s little I can say to reassure her here. The best I can do is to suggest and model strategies for navigating wide, systemic gender gaps. I have to wonder if this is really what my class is meant to be teaching her.

And so, on this day, I ask myself: should I go to work?

Finally, I think back to a recent assignment that, at least to my mind, provides tangible evidence to a different kind of gendered bias in software development–assumptions about who uses the software, and who this technology is for. To start turning students’ focus to the user, we develop various personae: documents that describe a single, fictional user who is meant to represent a particular user type. Per industry standards, each persona should include (at minimum) a fictional image, name, age, and description of their technological environment. We asked each team to produce a persona for their product’s primary user type. Of the 14 teams that completed this assignment, only one team produced a persona for a female user. Let me repeat that: only 1 team out of 14 explicitly imagined that software is for women.

And so on this day, I tell myself: I need to go to work.

Works Cited

“Administration and Faculty.” Georgia Tech Fact Book, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2015, http://factbook.gatech.edu/quick-facts/administration-faculty/.

Baer, Drake. “Google has an embarrassing diversity problem,” Business Insider, May 29, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/google-diversity-problem-2014-5.

Colt, Sam. “Apple releases disappointing employee diversity numbers,” Business Insider, April 12, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/apple-diversity-numbers-2014-8.

Crockett, Emily. “At least 3 school districts are canceling classes because of the women’s strike.” Vox, March 7, 2017, http://www.vox.com/identities/2017/3/6/14831114/school-districts-closing-day-without-a-woman-strike.

Houston, Gwen. “Global diversity and inclusion update: sharing our latest workforce numbers,” Official Microsoft Blog, Microsoft, Nov. 23, 2015, https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2015/11/23/global-diversity-inclusion-update-sharing-our-latest-workforce-numbers/#sm.0001ed1iz4i2aev0qhg1j4w6k4zfs.

Kosoff, Maya. “Facebook disclosed its diversity numbers, and they’re pretty bad.” Business Insider, June 25, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-diversity-report-2014-6.

Kosoff, Maya. “Here’s evidence that it’s still not a great time to be a woman in Silicon Valley.” Business Insider, Jan. 2, 2015, http://www.businessinsider.com/women-hold-just-11-of-executive-positions-at-silicon-valley-tech-companies-2015-1.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Table 209.10: Number and percentage distribution of teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools, by selected teacher characteristics: Selected years, 1987-88 through 2011-12.” Digest of Education Statistics. Institute for Education Sciences, 2013, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_209.10.asp.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Table 315.20: Full-time faculty in degree-granting post-secondary institutions, by race/ethnicity, sex, and academic rank: Fall 2009, fall 2011, and fall 2013.” Digest of Education Statistics. Institute for Education Sciences, 2015, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_315.20.asp?current=yes.

“Undergraduate Enrollment by College Ethnicity, and Gender.” Georgia Tech Fact Book, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2015, http://factbook.gatech.edu/admissions-and-enrollment/undergraduate-enrollment-by-college-ethnicity-gender/.

Zamudio-Suaréz, Fernanda. “Why one professor decided not to strike for International Women’s Day.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 8, 2017, http://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-One-Professor-Decided-Not/239439.