By Sarah Higinbotham, Fan Geng, and Dun Cao

Clik here to view.

Simon Russell Beale, National Theater, London, 2014

What does Shakespeare offer aerospace engineering majors, who often take eighteen hours of computational science, physics, and biochemistry in a typical semester? How does Twelfth Night — Shakespeare’s comedy about the flexibility of language and love — contribute to Georgia Tech students’ analytical skills? And how does King Lear, a tragedy about children who betray and humiliate their fathers, relate to Asian students raised in a culture committed to family honor? We hope to demonstrate that Shakespeare captures something of Georgia Tech’s distinct blend of multicultural and interdisciplinary diversity. According to a well-known Asian proverb, “There are a thousand Hamlets in a thousand people’s eyes”: one text, a thousand interpretations. Reading Hamlet, Twelfth Night, King Lear, and other plays has not only addressed why we study Shakespeare at Georgia Tech, it has illustrated the truth beneath the adage of “a thousand Hamlets.” This is evidenced in the ways that two engineering students interpreted Shakespeare through the lens of their native Chinese culture, and in the process, learned to identify open questions, grow comfortable with experimentation, synthesize perspectives, and communicate original ideas effectively.

World Englishes at Georgia Tech

As part of the Georgia Tech Writing and Communication Program, the World Englishes Committee seeks to raise awareness about different cultures’ norms and conventions within the framework of writing at Georgia Tech. We are not only interested in the challenges that non-native English students face, but also in the ways that multilingual students enrich English classrooms. In November 2014, the committee hosted a roundtable discussion with seventeen faculty and fifteen non-native English students. We particularly wanted to understand the students’ experience as writers, as well as the challenges they face navigating an institution whose customs are often foreign to their own. Our invited students from Malaysia, South Korea, China, and India shared their cultural perspectives on studying English at Georgia Tech.

The students related many complexities: classroom style differences (such as the freedom to disagree with the professor and fellow students), struggles to comprehend literature in English, and the often-frustrating tasks of expressing themselves clearly, both aloud and in writing. In particular, Dun Cao explained that in China, writing tends to be more implicit:

Rather than pushing our ideas forward, we imply them. We allow the reader to interpret the meaning. It’s also like this in our art. In Chinese art, we leave spaces in our painting and suggest a river scene with just a drop or two of water. We do not draw the entire scene. So we also write like that. We like to leave blanks.

Dun’s assessment of this difference resonated both with his fellow Chinese students and with the faculty present, who had often noted students’ hesitancy to defend their claims. All of the students at the Roundtable expressed that they wanted to read great works of English literature. But they also responded enthusiastically about interpreting Shakespeare, Melville, and Milton through their own cultural perspectives. Their idea led directly to Fan’s researched essay on filial piety in King Lear and to Dun’s book art project on Twelfth Night.

Beyond A Single Culture: King Lear Researched Essay, Fan Geng

Clik here to view.

Twenty-four Filial Exemplars, Guo Jujing (illustration from 1846 reprint)

Shakespeare’s King Lear is one of the most famous tragedies not only in western culture, but also in Asian countries, where it has been translated into many different languages and been played on many stages. It is a play about children who disrespect and betray their fathers. Chinese culture is rooted in the philosophy of Confucius, and the core value is “filial piety”: respect for one’s father. My challenge was to interpret the play’s own deeply rooted cultural heritage while also researching scholars from eastern countries, especially in China and Japan, where King Lear has perplexed eastern scholars for over a century.

One of the most important things that I learned from this project is that the literature review is the cornerstone of an academic essay. I found more than twenty articles on my topic (which I translated from the Chinese), and then selected articles based on how they would relate to my arguments. This experience enhanced my ability to find effective articles not only in English literature, but also my technical writing in the upcoming graduate school in Georgia Tech. It is invaluable treasure that I found in this project.

The other obstacle that I conquered during this work was how to accurately translate the concepts and ideas from traditional Chinese culture into English language, and then use them as a tool to interpret Shakespeare’s work. I examined three groups of King Lear’s characters from the perspectives of Confucius. I argued that “love” and “nature” are the needles that interweave between those characters. I concentrated my work on the “filial” concept rooted in traditional Chinese culture to interpret King Lear at a different angle, then analyzed the relationships between both the children-parents and chancellors-king from the three different levels of “filial” concepts that Confucius and Mencius advocated in ancient Chinese society for more than two thousand years. In this project, my abilities of critical analysis, integration of complicated information, and organization of key ideas and concepts were rapidly developed by trying to build the cultural bridge from Shakespeare’s work to the eastern culture.

Beyond the original work, the revision process of this essay was a good opportunity to enhance my standard English writing, to develop the sense of using MLA formatting, and to improve my understanding of basic concepts of western culture.

An Artist I Am: Twelfth Night Book Art, Dun Cao

English is not my mother tongue, which adds to the difficulties I have reading Shakespeare. It was extremely hard when I first read Twelfth Night: unfamiliar words, intricate sentences, barely understanding the plot. I asked Dr. Higinbotham for help, and as we talked after each class, I told her my discoveries and thoughts while she listened. I grew to understand and appreciate Shakespeare.

As one of my English 1102 projects, I studied book art at the Georgia Tech Paper Museum. I choose to define each main character in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night using Chinese art: a symbol, an element, to reflect my idea. Just as we talk and write in a reserved way, Chinese ink painting intentionally leaves blanks. The blanks are for readers to have their own thoughts. Also, Shakespeare’s characters are similar to characters in Chinese tales. They share the same spirit. For example, Viola disguises and reveals herself just as Mulan does. In my book art project, I paired Olivia, Orsino, Malvolio, and Viola with unique Chinese symbols that directly reflect their characters:

Orsino is a guy who sinks in his daydream of Olivia. Therefore the first page of my book has a peach tree (representative of love and arrogance in my culture) in a bright color (represents an unreal dream)

Viola’s page has a bell (represents that she misses her brother) and a jewelry box (represents that she disguises herself)

Malvolio’s pride is demonstrated by a peacock

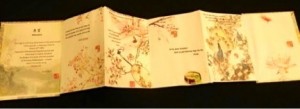

Clik here to view.

Accordion Book Art, Dun Cao, 2014

Book art was an interesting though challenging project for me. After the roundtable discussion about multilingual Georgia Tech students, I was busy thinking about cultural differences between where I came from and here. “Why not make my book art with characteristics from my own culture?” I thought. My question took me to my high school art class in China and the paintings that I appreciated there. Instead of directly portraying Shakespeare’s characters in Twelfth Night, I chose to do it in a more implicit way, using symbols like a peach tree, a jewelry box, a peacock, and a bell to express Shakespeare’s subtle characters.

Finding the Right Words

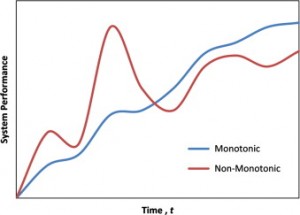

Our act of co-authoring this essay demonstrated the many complexities and benefits of multilingual, interdisciplinary collaboration. As we edited, Sarah pointed out to Fan that the initial subheading for his section, “Beyond the Monotonous Perspective,” might be confusing to an English reader. She explained that in English, “monotonous” means repetitive, boring, and uninteresting. Fan quickly agreed, and replied that he was thinking as an engineer: in math, a “monotonic function” is one that preserves a given order; it does not change its sign. Fan chose the subheading because he wanted to point out that his essay on filial piety in King Lear brings together several competing orders and, in fact, changes signs. He approached Shakespeare as a non-monotonic function that can have many possible turns within its given period. Sarah assumed the problem was related to their different native tongues. In fact, it resulted from their different academic disciplines: a thousand Hamlets between the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and the College of Engineering.

Clik here to view.

Monotonic and Non-monotonic Functions, Stanford Math Department

Fan’s essay on filial piety and King Lear first identified, then filled, a research gap. It also demonstrated his ability to bring together culturally diverse concepts. As an aerospace engineer, he will need to create new knowledge and collaborate with international partners. Dun’s minimalist art brings a new visual perspective to Shakespeare’s characters. In the development of his book art, Dun refined his ability to design and structure a project that imagines alternatives to existing approaches. These are skills that will serve him well as a mechanical engineer. As the three of us discussed a title to cohere our ideas, Fan and Dun quickly and simultaneously suggested “A Thousand Hamlets,” and introduced Sarah to a common proverb in their country — once again drawing on their Chinese perspectives to inform our shared experience. Our multilingual students bring their global and interdisciplinary perspectives into the English classroom: a thousand Hamlets, a thousand ways to interpret and recreate the texts we study together.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

About the Authors: Sarah Higinbotham is a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow who teaches early modern literature. She appreciates the thousand ways that her students have taught her to understand Shakespeare (and monotonic functions). Fan Geng graduated from the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering in May, 2015 with a Bachelor of Science in Aerospace Engineering, and will continue his PhD journey in Georgia Tech for the next four years. He is from Shijiazhuang, China and one of his favorite places is Crater Lake, Oregon. Dun Cao is in the Woodroof School of Mechanical Engineering, class of 2016. He is from Nanjing, China, and when he isn’t studying, you can find him playing video games.