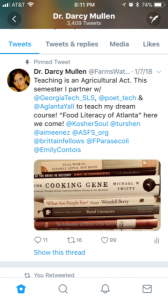

Clik here to view.

Pedagogy in action. Photo courtesy of the author.

SUMMER

“Once I remember looking into the freezer can the next morning and finding the leftover ice cream had all returned to milk. It was like the disappearance of Cinderella’s new clothes.” (Lewis 53)

Midway through my Spring composition course, “Food Literacy of Atlanta,” my students and I had the pleasure of holding a Q&A on Skype with Julia Turshen, author of Feed The Resistance (2017). When asked if she had a favorite cookbook, Turshen quickly named Edna Lewis’s The Taste of Country Cooking. Turshen explained that it isn’t just a cookbook—Country Cooking is a favorite because of the poetry Lewis brings to food. Lewis’ voice is experiencing a revival as we do better in articulating the central position of black women in American food history. A formative chef and food writer, Country Cooking has personal reflections on growing up in Virginia within and around its recipes. Divided by the four seasons, the reader encounters textured meditations on eating, cooking, agriculture, weather, family, culture, and love.

Clik here to view.

Photo courtesy of the author.

In the passage above, we have an example of Lewis’s poetics. This moment of opening the freezer door to look for the ice cream is imbued with anticipation, nostalgic disappointment, and despair. I would bet many people reading this have at some point either witnessed, or had, an ice cream-related crisis. Ice cream, the ephemeral stuff of fairy tales, is suddenly gone, turned into something much less magical. Discovering the failure of alchemy that had made the possibility of ice cream, Lewis confronts the ruined mess of deconstructed ingredients. Here, ice cream is something too good to last—like Cinderella’s gown. Food becomes a marker for time, transformation, and expectations. Food here, and always, is rhetorical.

Lewis’s poetic choices give us a way to understand the food at hand (ice cream, milk, custard, salt, etc.) as metonymic for a shared language with which to communicate cultural experiences. In this case, it is about the memory of summer and childhood in the American South. In that memory is a record of economics, food, climate, social practices, and mythology within a foodshed.

My essay follows Lewis’s poetic map of the four seasons; the signposts for Summer, Fall, Winter, and Spring through the 2017-2018 academic year. Two topics I return to in course design are recent Nobel Prize Literature Laureates and Food Studies in literature. While they may seem like two sides of totally different currency, a big thing they have in common is that both course topics ask, “What are ways literature is striving to make a better world?” Our learning outcomes extend to asking how we define that kind of better, and is it equitable, and/or sustainable. Lastly, given the role of communication in our primary texts, we investigate the role of aesthetics in the answers of all these questions. My classes were fortunate to be affiliated with Poetry@Tech, and we were fortunate to receive a pedagogy grant from the Writing and Communication Program. With additional support from Serve-Learn-Sustain, my students were able to interact with guest speakers and authors. All these opportunities were fortified with poetry as a discovery tool to engage with local and global connections, and food literacy in the classroom. In these classes, we used the form of the Exquisite Corpse, amongst other exercises, to help ourselves work to use poetry as a generative model for critical thinking.

FALL

“Unlike other seasons of the year, the coming of fall was looked upon with mixed feelings” (Lewis 144).

In the composition classroom, there are always mixed feelings towards writing. Poetry can discombobulate those already-mixed-to-begin-with feelings. In my fall course on Nobel Laureate Literature, we read books by the five recent winners. Prior to the announcement of Kazuo Ishiguro’s win last October, the most recent recipient, Bob Dylan, was awarded the prize “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Though I’m not on team Dylan personally, the award going to a songwriter offered us an opportunity to ask about definitions and boundaries of the genre of poetry itself, especially among this hodgepodge of Laureate writers.

Clik here to view.

Dr. Darcy Mullen presents for the Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain at Georgia Tech. Photo courtesy of the author.

The criteria for awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature is for work showing both “an idealistic tendency” and is “of greatest benefit to [human]kind” (Jewell 101; 103). Providing students with the judges’ own model of inquiry from the beginning of the course—to find and articulate an ideal tendency, to articulate what in a literary work is of benefit to humankind—can demystify poetry by providing an organizational tool for assessment, classification, and meaning-making. Students then encountered the Nobel laureates’ work in tandem with poetry written by the visiting poets performing at Georgia Tech’s Poetry@Tech events. The pairing of Alice Munro (2013 Nobel laureate) and Vijay Seshadri prompted discussions about what love makes us remember, and what forgetting make us love. The combination of Patrick Modiano (2014) and Victoria Chang asked us to consider the role of tone in trying to communicate memories. Together, Svetlana Alexievich (2015) and Tyehimba Jess provoked strong reactions about the need for bending genres to fit content. Students created Exquisite Corpses responding to the prompt of “what was of benefit to humankind, or an ideal tendency in these writings?”

In his short essay, “Why the Exquisite Corpse Works,” Alex Chertok explains a simple way to create Exquisite Corpses in the classroom; “each student writes the first line of a poem on a sheet of paper…. The line can be long or short, full or fragmentary.” Next, students move “the paper to the left; now holding her partner’s paper containing the first line, the student writes a second. Then…that student folds the paper so the first line is concealed and only her line is visible.” The results are surprising and insightful.

Consider this example created by my students:

How easily humans are drawn to war, which I swore to never write of again

War. While creating history it creates awareness

The darkness dissolved from the light, horrors were shown, the world was shocked.

The ideal tendency involves providing insight for the goodness of human kind.

People are innately good

suffering around every corner you turn

words on a page pale in comparison to voices in the street

stranded but safe in a surrounding, shiny security

thousands of lives changed

They lived in a different world and reality

Humans cannot justify their motivations for the atrocities put on humans

Alexievich provides a unique insight into realities

and I find it kind of funny

we drove the men mad, and then drove them out forever.

I read the poem back to the students. The first response to this activity is always, “I thought it was going to be a hot-mess, but it works.” So, why did it work? Some said it “worked” because it made what it means for writing to express an ideal tendency “click”; because students could identify the ideal tendency they were all getting at. Or it worked because it was like a class discussion, polyvocal, and with an elegance and abstract clarity that oral discussion doesn’t always have.

WINTER

“I was too young then to understand why so much time was spent in discussion. It was only afterward that I realized they were still awed by the experience of chattel slavery fifty years ago, and of having become freedmen.” (Lewis 227)

In January, I began teaching the course on food literacy. We worked with Serve-Learn-Sustain and community partners to focus on sustainability, community, food systems thinking, and food justice. We also worked with Poetry@Tech texts as a site for how aesthetics determines critical literacies of sustainability in our local space.

Among other materials, we read one of Wendell Berry’s most commonly referenced essays, “The Pleasures of Eating,” which echoes the humanistic and humanitarian ideals of the Nobel committee. In this essay we find what I call a new proverb for the rhetorical situation of contemporary food: “eating is an agricultural act.” Berry’s well-known quote points us to a complex historical reality. In the introduction to The Potlikker Papers, John T. Edge explains the necessity of reading Berry against the grain. We used Exquisite Corpses to articulate what we should be to reconsidering. I asked students to respond to the following passage from Edge via Exquisite Corpses:

“Eating is an agricultural act,” Kentucky native Wendell Berry once wrote. In the South, that equation has been fraught, for in addition to being virtuous work in which writers like Berry take justifiable pride, agriculture begat the region’s original sin: slavery. (2)

I read their poems aloud. Consider this one:

Original sin is a very weird concept

agriculture has led to inequalities

opening the mind to the surrounding world

and so grew the corn from labor

and there was a fluffy cat

As time conceals the scars of the past

In the first ten years of reconstruction things were good.

It was later efforts to retain slavery that caused the problems.

The traditions go back generations to use what we have here in front of us

to see the truth

the cornbread cried out with a little white puppy

the past may be dark

the present bears ill fruits of harmony

Surprise over the cohesion of the poem eventually subsided, to be replaced by an uncomfortable and consuming silence. In their poem, students saw movement between the past, present, and future represented as inevitable. Food became the location for having that conversation. This poem also had something that the others didn’t. Students explained that humor here created dissonance (what is a fluffy cat or a white puppy doing in a poem about justifications and legacies of slavery?). The dissonance worked for them because their awareness of the history of America and enslaved populations (and current forms of slavery in our food systems). Later, in Twitter essays, and live Tweets of Poetry@Tech readings, students would note the importance of accepting dissonance as a part of experiencing poetry. You can read their insights, in their own words, here. These student-observations come through particularly strong during readings by Aimee Nezhukumatathil and Christopher Collins (as well as Tarfia Faizullah’s written work).

SPRING

“There used to be a big sigh of relief when planting was over, but then we would plunge right into the work of cultivation . . . .” (Lewis 7)

My students and I are quite literally in the process of cultivating a podcast series with aglanta.org. Through support from SLS, and a community partnership with Atlanta’s Office of Resilience, my students created a series of podcasts about the lexicon of food in Atlanta and our contemporary conversations about our food systems. This project is happily moving into its second season. Taken as a complete collection, the listener moves through a varied terrain of stories, arguments, and information. Deliberately curated by class chronology (and not theme) moving through the collection from beginning to end has a listening experience that creates productive aesthetic dissonance. Stay tuned for the podcast webpage launch on aglanta.org to experience the textured turns with students’ food lexicons for yourself!

Clik here to view.

Dr. Darcy Mullen’s Spring 1102 course. Photo courtesy of the author.

I’m certain my students didn’t intend to engage either “what food words are of benefit to humankind?” or “what is the ideal tendency we encourage listeners to consider?” Nevertheless, all the podcasts strongly attend to one, or both, of those questions. Their research will carry on as a public resource for everyone who has a stake in food in Atlanta, as well as the aesthetics and poetics in those knowledge-areas. Additionally, the @poet_tech feed and the #ATLFoodLit hashtag will continue to be resources for conversation about the aesthetics and poetics of food rhetoric and food literacy in Atlanta.

Having had so much fun and learned so much from these classes, I’m thinking about how my pedagogical practices absolutely follow the school of thought articulated in Eileen Schell’s “The Rhetorics of The Farm Crisis,” published in the collection Rural Literacies. Towards the end of her chapter, Schell writes that “our human need for food means we all have a stake in agriculture” (118). It’s a system that does not leave a single person untouched. Schell explains that in the writing classroom: “critical literacy work” about food can help “[s]tudents. . .to understand the extensive network of community and global linkages that

currently shape our lives as food consumers and can begin to consider practices that will make those linkages more sustainable and equitable (118-199). This is a hope for the writing classroom to be a place for critical literacy work, or a place to gain rhetorical literacy about the connections that create our communities on local and worldwide levels. I want my writing classroom to be a space for students to develop a rhetorical toolkit for critical cultural literacies that includes poetry.

In using poetry as a discovery tool for both courses, many students said that it was a fun way to take notes, and that it made them want to do more with poetry. A number of students pointed out that these activities got to the heart of what the course readings were expressing, in a way they hadn’t thought of before. . .but they must have known more than they recognized if we were able to write it. They could not dispute their abilities to write as community, about rhetoric and poetics, and to demonstrate critical literacies. To use imagery from Lewis, I myself experience a big sigh of relief in this—that something new was planted in these classroom exercises with poetry. This semester, I’m excited to see what happens when we use poetry again to plunge back into the work of cultivating critical literacies. The proof is in the poem.

Works Cited

Berry, Wendell. “What Are People for?” What Are People For: Essays. Counterpoint, 1990.

—. “The Pleasures of Eating.” What Are People For: Essays. Counterpoint, 1990.

Chertok, Alex. “Why The Exquisite Corpse works,” Plougshares Blog, 21 Jun. 2015, http://blog.pshares.org/index.php/why-the-exquisite-corpse-works/.

“Play Exquisite Corpses.” Academy of American Poets, 7 Apr. 2004, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/play-exquisite-corpse.

Edge, John T. The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of The Modern South. Penguin, 2017.

Jewell, Richard. “The Nobel Prize: History and Canonicity.” Vol. 33, No. 1 (Winter, 2000), pp. 97-113, The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association. DOI: 10.2307/1315120

Lewis, Enda. The Taste of Country Cooking. Knopf, 2017.

Mullen, Darcy. ““The Times They Are A Changin”: Teaching Bob Dylan, the Nobel Laureate Winner.” Pedagogy and American Literary Studies, 22 Jan. 2018, https://teachingpals.wordpress.com/tag/bob-dylan/.

—. There’s No Space Like Home: Locavore Writing and the Rhetorics of Place. Dissertation. University at Albany, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1904921558/?pq-origsite=primo.

Schell, Eileen. “The Rhetorics of The Farm Crisis.” (77-119) Rural Literacies. Edited by Kim Donehower, Charlotte Hogg, and Eileen Schell. Southern Illinois UP, 2007.

Turshen, Julia. Feed The Resistance: Recipes and Ideas For Getting Involved. Chronicle, 2017.

Twitty, Michael W. The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. Harper Collins, 2017.

The post Teaching in All Seasons: Poetics, Ideal Tendencies, and Food Literacy appeared first on TECHStyle.